On the China∩Quantum Newsletter

If you are new here, this is a good place to start

Welcome to the China ∩ Quantum Newsletter!

This newsletter explores quantum tech in China and how it affects, and is affected by, the wider world. Mostly from an S&T innovation policy angle, covering both current events and big questions.

This and most pieces in this newsletter are not technical, but general familiarity with quantum technologies is implicitly assumed. Start with this [1 ] footnote for a short primer on quantum technologies if you are new!

In the following, I introduce some guiding ideas and motivations for this newsletter.

I argue that English-language discourse on Chinese quantum S&T is lacking (scroll down for some examples of typical misperceptions).

I introduce my broader view on the competition in quantum technologies, introduce the framing of “access asymmetry”, and argue why the deepening quantum bifurcation is highly concerning.

Why: Quantum in China matters globally, but English-language discourse is lacking

The future transformative potential of quantum technologies is widely recognised, with quantum not just a hot topic for STEM students but also a priority for decision-makers in industry and policy. (This transformative future potential—yet largely unrealised and by no means guaranteed—is assumed here.)

Quantum technologies are subject to intensifying technological competition, framed as key2 to future economic competitiveness and military power.

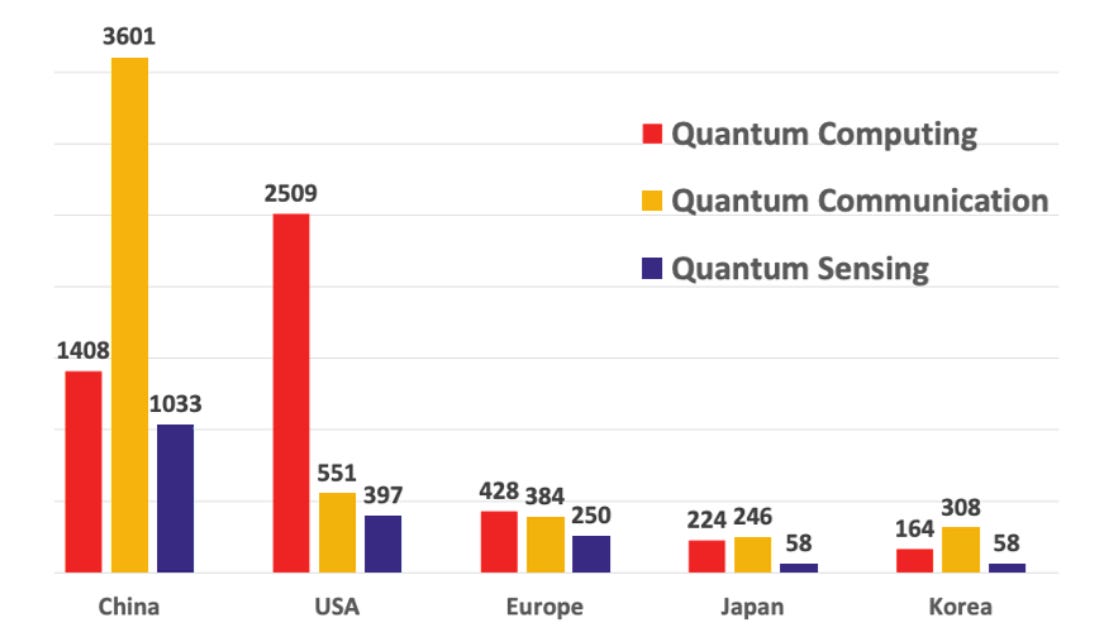

China plays an important role in the global development of quantum technologies. China leads globally in the deployment of quantum cryptography and has recently undertaken significant initiatives in quantum sensing. China is widely considered behind the US in most quantum computing modalities, although for some, this view has become more shaky given the comparable performance of Zu Chongzhi No. 3 (by USTC) with the Willow quantum chip (by Google). Furthermore, in metrics such as number of scientific publications, citations or patents, aggregate quantum output in China is often close to or surpassing that of the US. Some of the most famous quantum experiments in recent years, such as the Micius satellite or the world’s second “quantum advantage” quantum computing experiment, were realised by Chinese researchers.

Yet, English language discourse on quantum in China is often lacking, oscillating between hype and sensationalization on one extreme, and disregard on the other. Take the example of patents (figure above), which can be interpreted to show China dominating global patenting (if domestic patents are considered) or lagging far behind the US and Europe (if only patents issued by at least two patent authorities are considered).

English language discourse is often lacking

A recent piece3 in The Wire China highlights the alarmist “quantum panic” frequently found in English reporting of quantum breakthroughs in China. The increasingly securitised view—part of the wider US-China tech competition, through which quantum technologies are seen—incentivises articles that amplify extreme claims, such as related to cryptographic breakthroughs (which often turn out to be misleading) or military applications. Despite my criticism of excessive alarmism, US-China competition in quantum does matter. It could have grave consequences (see “quantum bifurcation” below), necessitating grounded, cool-headed analysis that cuts through the noise. This blog aims to be a platform for serious thoughts and discussions about quantum in China and address popular misperceptions and discrepancies.

Take the following examples of misperceptions or discrepancies that I hope to discuss further at some point:

“The Chinese government spent 15 billion USD on quantum technologies.” (E.g. here, here, here …) I want to write a separate piece on this at some point. For now, this quote from Olivier Ezratty‘s book also expresses my view on this: “It is tiring to see these unchecked and non-official numbers since China’s government has never communicated in a consistent and consolidated manner about its investments in quantum contrarily to most developed countries. Why are these false numbers circulating broadly in the Western world without being checked?”

“There is no meaningful quantum industry in China, everything happens top-down in state-directed laboratories.”

This point is more subtle, as state assets and publicly funded laboratories do indeed play a very important role in China’s development of quantum technologies. However, the focus on government-led labs and top-down planning risks prematurely disregarding other efforts, such as incentives and support measures for private quantum entrepreneurs4. I think this is one of the reasons why the number of quantum companies in China is often significantly underestimated. For example, a 2024 ITIF report on China’s quantum ecosystem concludes that “only around 14 private-sector firms can be identified as making significant contributions to quantum technology.” On the other side, CAICT—an important think tank under the PRC’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology—estimates the number of Chinese quantum companies at 107 in 2024.

“Chinese quantum research is highly sensitive and deliberately isolated.” See for example this Economist article or the aforementioned ITIF report. The reality is more nuanced. Overall, this author would argue that the Chinese quantum sector is currently less securitised and tightly controlled than in the US. Definitely in the case of academia, where Chinese institutes and conferences still aim to internationalise. Vice versa, Chinese quantum researchers struggle to obtain visas for conferences in the US (and some other Western countries) or face hour-long customs interviews. Official controls on Chinese quantum tech are also relatively modest5, at least in comparison to the US, which established a broad control regime including 32 PRC quantum additions to the entity list, comprehensive and internationally coordinated export controls on quantum computing (Sep 2024), outbound investment controls (Oct 2024) and import screenings. China’s Ministry of Commerce actually officially encourages foreign business cooperation in quantum technologies, and Xi recently highlighted quantum technology among cutting-edge fields in which to “cultivate incremental cooperation” between China and Germany.

China’s international isolation in the field is at this point of time more a consequence of successful US containment than deliberate Chinese isolation. Are there also Chinese quantum labs and corporations with tightly controlled access? Are quantum strategies and funding guidelines inaccessible to outside analysts? Is civil-military fusion a real thing? Sure, and all are significant. However, this does not mean that China’s overall quantum *strategy* is insular; rather, it combines (sometimes conflicting) efforts of self-reliance and integration into the global S&T ecosystem.

So far, I argued that quantum in China matters and English writing on it has room for improvement — plenty of reason to start a blog on this topic!

But there is more to my motivation, and it is related to the bigger picture in which I see international quantum competition.

The big picture view

Balance an “access asymmetry”

I believe that, in the field of science and more broadly S&TI, the last decades have seen a consistent access asymmetry between China and “the West”: A large flow of young talents from China to the West, some of whom return to China as highly educated graduates, researchers, and industry professionals. Much attention and often reverence are paid by Chinese observers to developments and actors in the West. And of course, there were also many cases of direct technology transfer (sometimes voluntary, sometimes “forced”). This access (and willingness to leverage it) resulted in a significant flow of knowledge and practices from the West to China.

I call this an access asymmetry due to the lack of equivalents in the reverse direction. Western students in China? Dwarfed (I guess 10x+) by Chinese students in the West. Attention to S&TI in China? Oscillating between ridiculing and sensationalising, with too little first-hand analysis.

This access asymmetry long made sense, a natural arbitrage resulting from vast development gaps. It makes less sense today, after China’s development rapidly progressed during the last decades. Indeed, there are some sectors in which the asymmetry likely started to equilibrate, or even reverse already. In industries where Chinese companies expand abroad (e.g. battery plants in Europe) or foreign corporations recognise access to China not just as a source of revenue, but also as a source of technology and best practices (e.g. German car makers).

In the field of quantum technology, this access asymmetry is likewise obsolete, as leading quantum science and technology is realised in China. Yet, in some ways, it still persists (look at student flows, for example).

The expansion of Western export controls and other technology restrictions and research security measures aimed at China are partly because this access asymmetry was out of touch with the underlying state of capabilities. The dual-use applications and “force-multiplying” potential of quantum technologies furthermore make Western policy makers highly uncomfortable with a continued asymmetry. Controls aim to rebalance by reducing China’s access. I believe that, instead, measures to increase access to China’s S&T ecosystem and allow more symmetric technology diffusion should be more widely considered by Western policymakers.

In this sense, this newsletter hopes to make a small contribution by increasing access to quantum in China through open-source analysis and building bridges between both sides of the Great Firewall.

Why is this important?

The long view: Quantum bifurcation?

In a sense, technological bifurcation, i.e. decoupling into two separate ecosystems—one Western and one Chinese—is already taking shape in commercial quantum technology today. Go to any quantum business event/conference in a Western country, and you are unlikely to find Chinese quantum companies (the reverse for events in China-based venues). Worried about further political intervention and controls, Western quantum companies try to keep “clean” of any Chinese involvement. Even hiring Chinese nationals6 can be a concern, don’t mention business with China-based quantum companies (many of which are on the US entity list anyway). Export controls and outbound investment restrictions keep US capital, hardware and software out of China’s quantum supply chain.

These measures are temporarily slowing down China’s progress, but they also supercharge localisation efforts and diminish foreign participation in and knowledge of China’s quantum developments.

The importance of collaboration for academic quantum science is widely recognised by both the West and China. Yet, even here, joint statements or agreements for international quantum collaboration are limited to a pool of countries closely aligned with the US. Quantum science is still highly international and collaborative, but it is becoming increasingly securitised. Several restrictions now affect quantum research, mostly, but not exclusively, initiated by Western countries with a view to China. These include visa restrictions or long customs interviews, investigations (China Initiative…), approval requirements (e.g. for travel or certain interactions), security screenings (e.g. of incoming students at ETH Zürich), grant scrutiny for foreign collaborators (e.g. DoD, DoE, NIH) and institutional hurdles among a wider trend towards research security. I have done preliminary research7 which shows that the topical composition of quantum research in China and the US has already started to diverge, reversing a longtime trend during which it became more similar. Even academia is feeling pressure to decouple in quantum.

Absent major political shifts, I expect the larger trend of quantum bifurcation into Western and China-dominated ecosystems to continue and become more entrenched over time.

Maybe, this expectation of bifurcation is too simplistic and neglects countries from the Middle East, ASEAN or BRICS that are both willing and able to integrate and bridge both spheres. Maybe, instead of bifurcation, we will see a replay of semiconductors during the Cold War, during which one country leads and the other desperately tries to catch up and imitate.

I would be happy to forego the bifurcation scenario, as I believe the consequences could be grave.

Imagine the following future: A technology, as foundational to information infrastructure as microcontrollers, matures over decades in two separated Innovation Systems. Unlike most other discussions of decoupling, this separation happens at a very early stage of commercialisation (after all, few quantum startups existed prior to 2018, which was also the year the US-China tech competition really started to get going!).

In the resulting bifurcated quantum world…

What happens after quantum standardisation efforts fail to produce consensus and lead to incompatibilities? Besides economic costs and slower progress, such incompatible standards could increase the likelihood of divergence in the technological paradigm, leading the US and China down different tech trees (think QKD in China and PQC in the US, or quantum computing modality A in China but B in the US).

How can we responsibly regulate dual-use quantum applications, like advanced cryptography-breaking or artificial design of chemical substances? How to coordinate on non-proliferation and abuse? Think of something like AI safety dialogues, but to establish guardrails on the use of a cryptographically relevant quantum computer (with all the havoc it could wreak through its decryption capabilities) instead of advanced AI systems.

How can we establish trust and safety dialogues if one side achieves a secret, decisive quantum breakthrough? Such an asymmetric capability gap could be highly destabilising, potentially leading to miscalculations or pre-emptive actions among mistrust. This would be exacerbated by limited insight into the developments of the counterparts, few supply-chain interdependencies, and possibly different technological paradigms.

For Western policy makers: How to maintain insight into China’s quantum ecosystem, and create pathways through which Chinese technical advancements or new directions can be noticed, and diffuse to the Western ecosystem?

Personally, I am worried about such a bifurcated quantum world, which is one reason why I am sceptical of excessive restrictions and securitisation of quantum technology. Rather, I would like to see more measures towards making technology diffusion bidirectional, rather than no diffusion at all.

In any case, if quantum bifurcation is the world we are moving towards, then informed and foresighted decision-making is all the more important. Another reason for this blog (the others were: improving English language discourse on this topic and building bridges).

What: Quantum in China and its interplay with the world

What will be covered in this newsletter?

Everything related to both quantum science and technology innovation and China. How does Chinese quantum S&TI affect, and is affected by, the wider world?

Expect quantum bifurcation (export controls, policy initiatives, international governance) and China’s openness (or lack thereof) to international collaboration in quantum to be recurring areas of interest. I also hope to occasionally write about current events or new developments, and maybe more technical deep dives.

When:

Whenever I find time and inspiration to write something that feels meaningful (feel free to send suggestions).

Hence, there is currently no fixed schedule. Expect fewer than weekly emails. If I am busy, there may be nothing for months. So no spam!

Who:

Elias X. Huber, your humble author; find me on LinkedIn. I will likely be based in Singapore for the foreseeable future. Reach out if you are around!

I come from a theoretical background in quantum information (master’s at ETH Zürich, research on quantum computing algorithms at CQT Singapore), but took the unusual step to follow it up with a 2-year masters in China Studies (Yenching Academy) at Peking University.

I worked in consulting in the past and am always open to discussing interesting ideas or projects (note, however, that I do not accept paid work from government entities).

The China∩Quantum newsletter is currently fully free, will generally reference sources, and attempt to provide reasoning transparency. But, as this is a blog, I express my own biased opinions. I am writing this both as a personal learning opportunity and to constructively inform the English-language discourse on this narrow topic. Let’s see where it goes. Happy to have you along.

Quantum technologies could one day become integral to how we sense (quantum sensing), transmit (quantum communication) and compute (quantum computing) information. While mostly limited to research or expensive specialist equipment today, they could become foundational to our information infrastructure decades into the future and have important security implications. In the 2024 report of the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission to Congress, under the heading “Quantum Information Science: The Next Frontier of U.S.-China Technology Competition,” quantum technologies are described as potentially paradigm-shifting.

Sometimes referred to as the “second quantum revolution,” quantum technologies rely on the precise manipulation of information on a very small scale, described by the laws of quantum mechanics. This information could be carried in individual electrons or particles of light, whose quantum mechanical states can interfere like the acoustic waves in your noise-cancelling headphones. They can also be entangled, i.e. correlated in a spooky non-local way, which is where the parallels to your headphones stop. Conceptually, quantum technologies leverage access to states, and operations on them, which are counterintuitively different from our deterministic interaction with the world–and which can bring practical advantages.

Quantum computing receives the most investments and hype, with people expecting applications in simulating nature, solving optimisation problems and, maybe, improving machine learning. Timelines for “useful quantum advantage” vary by who you ask. If you ask experts about breaking currently widely deployed cryptography in the next 15 years, according to a survey by the Global Risk Institute (2023) “a majority of respondents assigns to the existence of cryptographically relevant quantum computer an about even likelihood or better.” If you take somewhat credible company roadmaps, quantum computing could outperform classical computing in some meaningful tasks as early as the late 2020s.

Most quantum technologies are still at an early R&D stage, except for some sensing and cryptography applications, and much of the worldwide research efforts happen collaboratively in academic settings. However, leading-edge applications and hardware developments increasingly occur in start-ups (low billions of annual VC investments) and large tech companies (IBM, Google, Microsoft, …).

Besides academic and commercial efforts, policymakers are paying more attention (and money – est. USD 42 billion worldwide public funding to date) to quantum technology, aiming to support local innovation. Quantum technologies are prioritised both because of their (potentially) foundational role to the economy and society, as well as due to their national security implications. [For an overview of national quantum initiatives, see here]

Personally, given the early stage, I see the long-term outlook as very uncertain: Maybe, in 30+ years we indeed live in a world where millions of quantum sensors, connected by quantum networking infrastructure (“quantum internet”) to data centres full of quantum computers; maybe, quantum technologies will instead remain expensive specialised tools; or maybe, fault-tolerant quantum computing will remain completely out of reach. However, with worldwide efforts and expectations, the parallel pursuit of many different technical avenues and some optimism among the community, it seems hard to completely dismiss a long-term future where quantum technologies will be impactful. If history is any guide, the greatest impacts may not yet be on anyone’s radar.

[self-plagiarised from here]

Whatever your favourite term, you will likely find quantum listed: Emerging and Critical Technology, Critical Technologies for Economic Security, Future Industry (未来产业), Critical and Core Technology (关键核心技术) …

(for which I gave some comments)

More on this in a piece I published on ChinaTalk, for example: “Looking forward, USTC has recently piloted a new model for transferring university IP to commercialisation-focused researchers. Instead of shares in the company, the school obtains access to future benefits negotiated in advance — for example, a fraction of the company’s profit. Research at USTC also benefits its business alumni: Through bi-directional recruitment and frequent exchange, academic laboratories gain access to professional equipment and organisational practices.”

Mostly limited to quantum cryptography, some cryogenics and some use cases of quantum sensing.

This is significant, as around half of quantum-related graduates in the US are foreigners (and I would guess that Chinese nationals used to make up the largest share).

Which I hope to publish at some point in the future.

woo go elias! would love to have you guest post something for chinatalk!